Student caught in IRA bomb blast revisits the scene for art project

Date 10.05.2018

10.05.2018

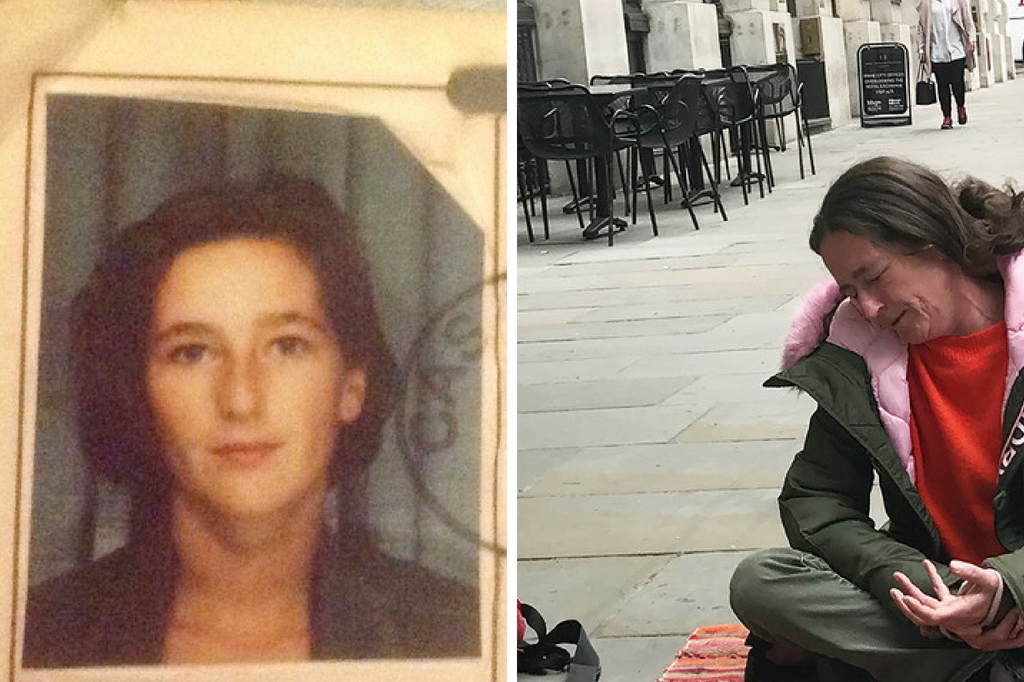

Jules Bishop was one of 45 people caught in the blast of an IRA truck bomb in the City of London in 1993.

On the 25th anniversary of the Bishopsgate bombing, which claimed one life, destroyed a church and wrecked Liverpool Street station and the NatWest Tower, Jules made an emotional return to the scene of the explosion.

Currently studying Fine Art at the University of Northampton, she used the mediums of video and performance to mark the anniversary.

Jules’ video piece combined the moving image with appropriated pixelated news report footage of the incident and finished with an alternative, mesmeric account of the bombing. The audio to the video was a testimony written the day after the bombing, by her friend, who was also caught in the blast, interspersed with uncomfortable traumatic disturbances and silence.

Watch it below:

It was broadcast on a giant screen on the back of a mobile digital advertising van, which was driven around various locations in and around Bishopsgate, on the anniversary.

The project, titled ‘If I Hear a Loud Bang, I’ll count to 10 slowly then walk towards it’, also saw Jules take part in a two-minute visceral performance at the exact site where she and her friend were when the bomb went off: 10.27am.

Later on that evening, Jules attended a memorial service at St Ethelburga’s church led by Richard Chartres, Bishop of London and attended by Sir John Major and the Irish Ambassador, Adrian O’Neill.

Here, Jules talks about the blast, the effect it has had on her life, and how her art has helped her to come to terms with the terrorist attack.

“I was in my final year of studying French at London Guildhall University in 1993.

“There were bomb scares all the time, it was almost normal. I was sitting my final exam in Tower Hill after the bombing and there was one. We heard a siren and I found I couldn’t write. I looked down on the paper and my writing had turned into a series of lines.

“My friend and I were on the same course, and we both worked part time in a wine bar, in The City. We didn’t normally work weekends, because there wasn’t enough trade for the bar to open, but the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development was holding a conference so there was going to be plenty of business that day. So we set off to work together on the Saturday morning.

“When we got to The City, there was a bomb alert and streets had been cordoned off, so we were walking around, trying to find a route to the bar.

“The blast happened about 300 metres from us. There was this huge vacuum before the explosion, like a deep inbreath and I just had a feeling of impending doom. It was a strange sensation, I can best describe it as that moment between the guillotine sliding down before it cuts the head off, or the time between a bullet being fired and it hitting its target.

“I don’t really remember the actual blast, but after it went off I ran to a building and my friend shouted that the windows were coming down in the street, so I ran the other way, and I think she saved me from bad injuries or worse.

“After that we both just ran. A mounted policeman found us and told us to run to Bank station. We got there and I phoned my mum and my flatmates. We then wandered aimlessly around the streets – we were shellshocked.

“While my friend had some cuts from glass, we were otherwise unhurt, physically, but I’ve lived with the emotional trauma ever since.

“When I was growing up in the 1970s and 80s, in Henley, I made my mind up that all of the terrorist groups in Ireland and Northern Ireland were as bad as each other. They seemed to have caused an equal amount of civilian casualties.

“After the bomb, I initially had intense hatred for the IRA, but as time went on, I went through a period of sympathising with them. I mean, how can they go to the extreme lengths of killing and injuring innocent, unless they have a very good, valid cause.

“My feelings changed again and now I’m back to thinking the IRA were just as bad as all of the other terrorist organisations. But I bear no malice towards them, that would just consume me in the end. My philosophy is that they did what they did and I’m here doing what I’m doing.

“For the 25th anniversary, I knew I wanted to be in the same spot that I was when the bomb went off. To really feel it. It felt like a triumph. I’d gone from a survivor, to a thriver and I hope my project will give hope to those who have suffered with trauma. I’m proud of it, it was important.”

For more details about Jules’ project, visit her website.