Our food supply isn’t about to collapse – but there’s a much larger challenge to come

Date 1.04.2020

1.04.2020

As the COVID-19 pandemic takes hold, the UK’s food supply chain is coming under increasing pressure. While the chain can cope with current levels of demand, the industry needs to adapt quickly for the ‘post disaster’ scenario that’s coming Its way.

Here, Liam Fassam, Associate Professor In Food Supply Chain Management at the University of Northampton, and Director of the Institute of Logistics, Infrastructure, Supply & Transport, gives his insight into the current and future challenges the food supply industry faces.

This article also forms the basis of a story on The Grocer website.

As the food supply chain suffers an unprecedented ‘supply chain shock’, predominately caused by panic buying, the eye has been taken off the ball with regards to post-disaster recovery.

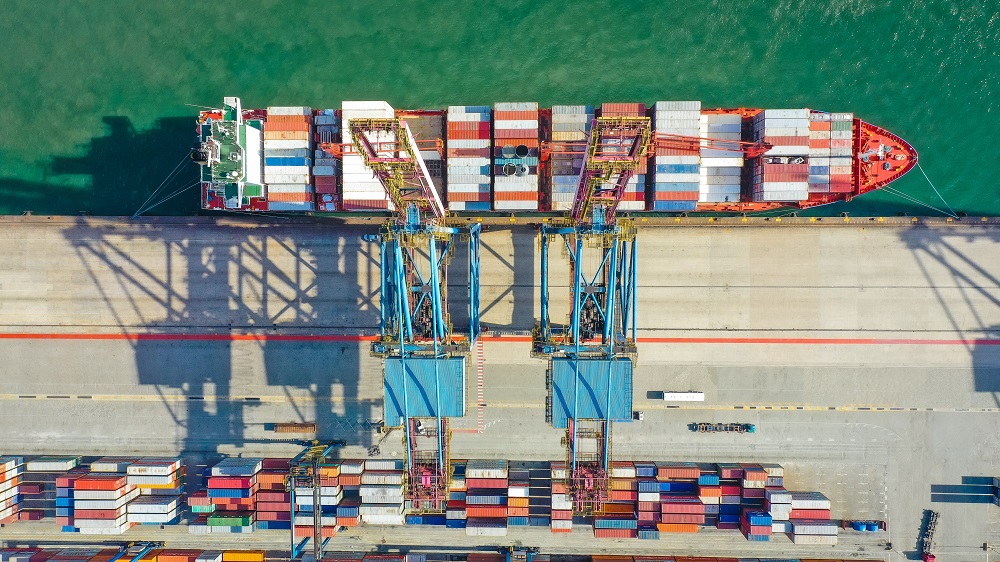

Much of the food and drink consumed in the UK comes from outside its borders, and this is of no surprise given our year-round approach to cuisine, which has benefits both locally and globally.

However, with the food service sector grinding to a halt with mass closures, some suppliers will be winding down stock levels to mitigate against obsolescence (date code issues). As self-isolation comes into effect across Europe, other production plants are struggling to meet demand due to diminished output.

That said, food supply chains are incredibly agile and the workers within them are unbelievably innovative. So, while it sounds like a broken society scenario, the schedules will level quickly and flows will be managed. Panic buying will cease and the shock to the supply chain will reduce.

Perhaps this is where the message to the general public has been lost and requires greater positing. We are not on the brink of collapse, and in fact years of farm to fork collaborative working is now coming to the fore.

But there is a much larger challenge yet to come. Much of the fresh food supply chain is planned 18-months in advance – such as planting seed, breeding cattle etc. When crops and livestock are ready to harvest or to slaughter, it simply has to happen. You cannot make wheat grow slower, or animals develop at an unhurried rate. Therefore, these products must be processed through the supply chain. If they are not used due to a production plant being on lower capacity, the raw material will go to waste.

Thus, it is incumbent on the wider food industry, both retail and food service, to review their holistic food supply chains and find alternative routes to market for these products. This could be instigating greater use of donation-based food supply chains (such as food banks) which are struggling through this crisis. Reviewing regions and diverting resource globally to areas that can utilise products in a meaningful and sustainable manner. Or adopting different practices of storing to slow down the ageing process associated with date code.

If such approaches are not undertaken, the ability for the food supply chain to switch back at pace will be massively curtailed. Farms will run low on resource (including funding) and there will be a decreased amount of raw material available.

These are trying times for all, but to protect the social value that the food supply chain gives in delivering local jobs, skills and economic contribution to a nation’s GDP (local and global) two things need to happen. The message needs to be reinforced that the food supply chain is excellent at coping with significant change, whilst upstream actors, such as farmers and manufacturers, need to be protected, not just with cash, but with sustainable routes to market.

Photo by Photo by sergio souza on Unsplash.